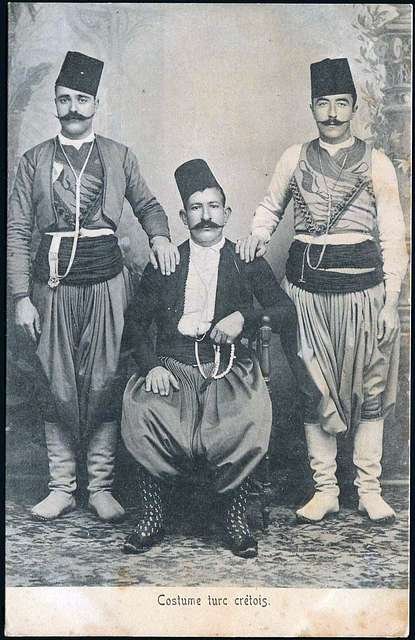

The history of Crete holds many fascinating stories, but few are as remarkable as that of the Cretan Crypto-Christians (Κρυπτοχριστιανοί – Kryptochristianoi). These resilient Cretans lived extraordinary double lives – publicly appearing as Muslims while secretly preserving their Christian faith during Ottoman rule. From hidden churches in mountain caves to secret codes passed between families, their incredible story of survival and cultural preservation remains one of the most captivating chapters in Cretan history.

Setting the Stage: A Time of Change

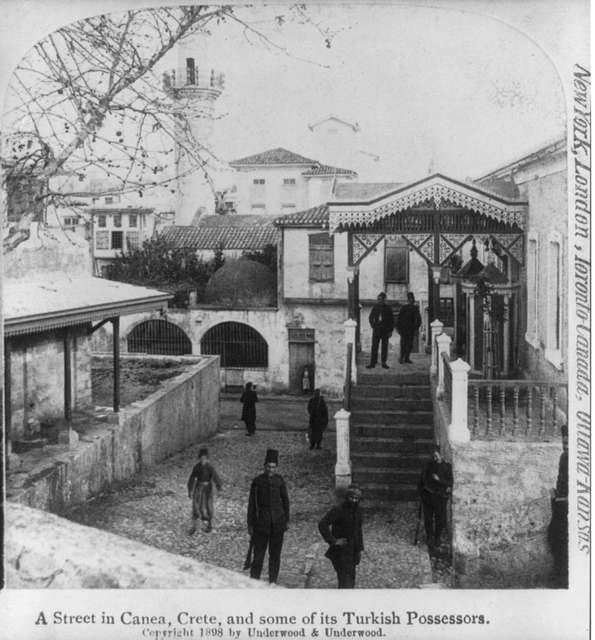

The path to this hidden existence began with what would become the longest siege in history. The Ottoman conquest of Crete lasted an astounding 24 years (1645-1669), fundamentally reshaping the island’s religious landscape. In the face of these changes, many families made the difficult choice to maintain a double life rather than abandon their ancestral faith or leave their homeland.

The story of these Crypto-Christians spans generations and touches every aspect of life on the island. They didn’t just preserve their faith – they created an entire parallel culture that would profoundly influence the history of Crete for centuries to come.

1. The Hidden Churches of Kapetaniana: Sacred Spaces in the Shadows

Perched at a breathtaking height of 800 meters in the Asterousia Mountains, the village of Kapetaniana served as one of the most remarkable sanctuaries in Cretan history. This dramatic location, offering stunning views over the Libyan Sea, wasn’t chosen by accident – its natural isolation provided the perfect cover for preserving Christian faith during Ottoman times.

At the heart of this mountain refuge stands the historic Monastery of Vathmou, later known as “Panagia of Kyrie Eleison.” This wasn’t just any monastery – it became a powerful spiritual center where ancient Byzantine traditions quietly flourished despite Ottoman control.

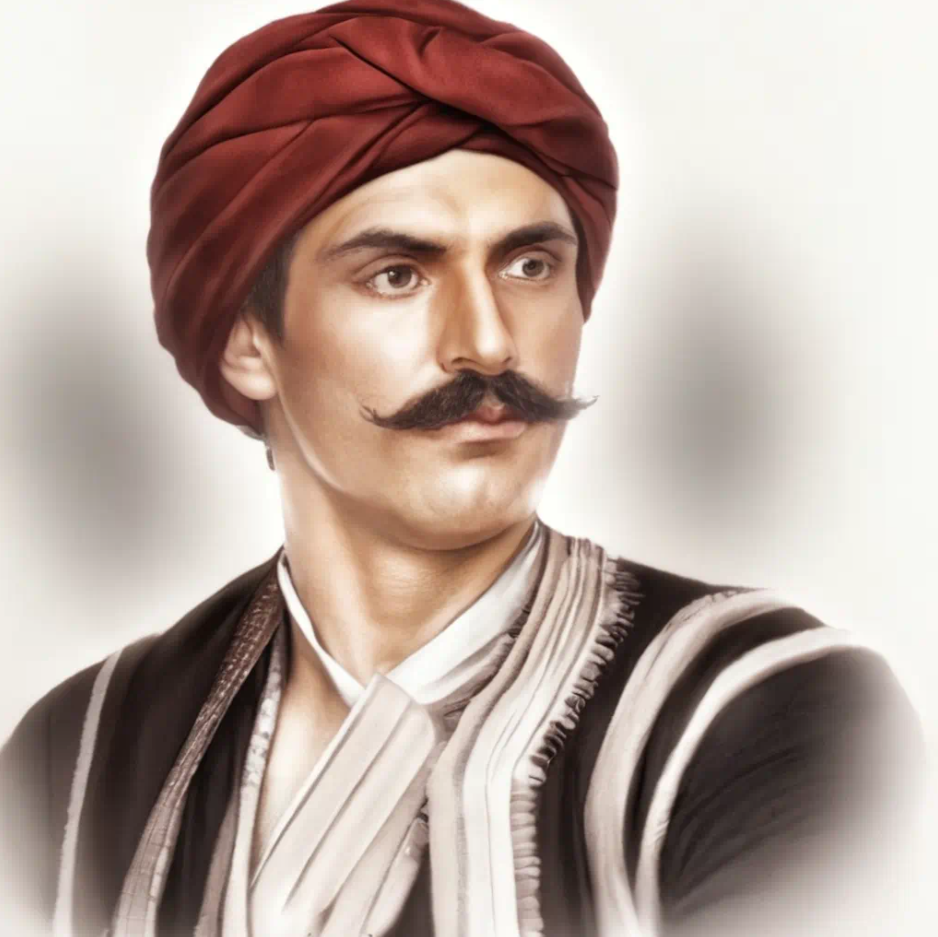

The monastery’s significance grew even stronger after fighters from Sfakia established themselves in the village following the Daskalogiannis revolution – – a brave but ultimately tragic uprising in 1770 led by a wealthy Sfakiot merchant who gathered 2,000 well-armed men to challenge Ottoman rule on Easter day. Though the promised Russian support never materialized and Ottoman forces suppressed the revolt, the revolutionary spirit lived on in places like Kapetaniana.

The religious architecture of Kapetaniana tells an extraordinary story of faith and ingenuity:

- The Church of Panagia, dating back to 1401-1402, showcases remarkable murals that have survived centuries

- The Church of Archangel Michael features impressive frescoes that quietly preserved Christian art

- Multiple Byzantine and post-Byzantine chapels dot the landscape, each with its own hidden history

The area became particularly significant as a refuge for Anterrites theologians and a center for Hesychasm, an ancient tradition of contemplative prayer. These sacred spaces weren’t just places of worship – they were masterpieces of religious camouflage, allowing the faithful to maintain their traditions while avoiding detection.

2. Double Lives and Secret Identities: The Kourmoulis Story

Among the many fascinating tales of Crypto-Christians in Cretan history, the story of the Kourmoulis family stands out as a remarkable example of survival and adaptability during Ottoman rule. Settling in the village of Kouses around 1680, this prominent family perfected the delicate art of maintaining dual identities – a practice that would shape their lives for generations.

The Kourmoulis family’s influence grew steadily over the years. While outwardly practicing Islam and serving as Ottoman officials (beys and aghas), they secretly preserved their Christian faith through careful planning and discretion. Their success in maintaining this double life was so complete that by 1821, their extended family network had grown to include approximately 100 related families in the Kouses area.

Today, visitors to Kouses can still see physical evidence of this dual existence in the impressive Kourmoulis Towers. These Venetian-style structures, complete with battlements, warehouses, and most remarkably, a basement containing a hidden church dedicated to Saint Pelagia, served as more than just homes. Here, in secret, the family performed baptisms, weddings, and Holy Communion. The towers also played a strategic role – Michael Kourmoulis, a key family figure born in 1765, was known to host Turkish officials in these very towers while simultaneously organizing resistance activities.

The Kourmoulis family operated on multiple levels to maintain their influence and protect their community:

- Used their high-ranking Ottoman positions (beys and aghas) to gather intelligence

- Maintained the hidden church of Saint Pelagia for secret Christian ceremonies

- Strategically hosted Turkish officials while organizing resistance

- Provided shelter and assistance to other Christians during occupation

- Developed extensive networks with other crypto-Christian families

The family’s story took a dramatic turn during the Greek Revolution of the 1820s. Michael Kourmoulis emerged as a crucial leader, helping to organize and lead Cretan forces in the 1821 uprising. Believing that Ottoman rule was finally coming to an end, the family, along with other crypto-Christians, made the bold decision to reveal their true faith. However, this choice proved premature – when the Ottomans regained control, the family was forced to flee to Hydra, where Michael Kourmoulis died in 1824.

Throughout their time in Kouses, the Kourmoulis family maintained an extensive network of communication with other crypto-Christian families, helping fellow Christians during the Ottoman occupation while maintaining their careful masquerade. Their story serves as a powerful reminder of how deeply rooted faith can be, even when forced underground. The Kourmoulis family’s legacy stands as a testament to the extraordinary lengths people will go to preserve their true identity and beliefs.

3. Monasteries: The Beating Heart of Christian Resistance

In the tapestry of Cretan history, monasteries like Arkadi and Preveli emerge as more than just religious institutions – they were sophisticated centers of resistance, education, and cultural preservation during Ottoman rule. These monasteries became the lifeline that kept Christian traditions flowing through the veins of Cretan society.

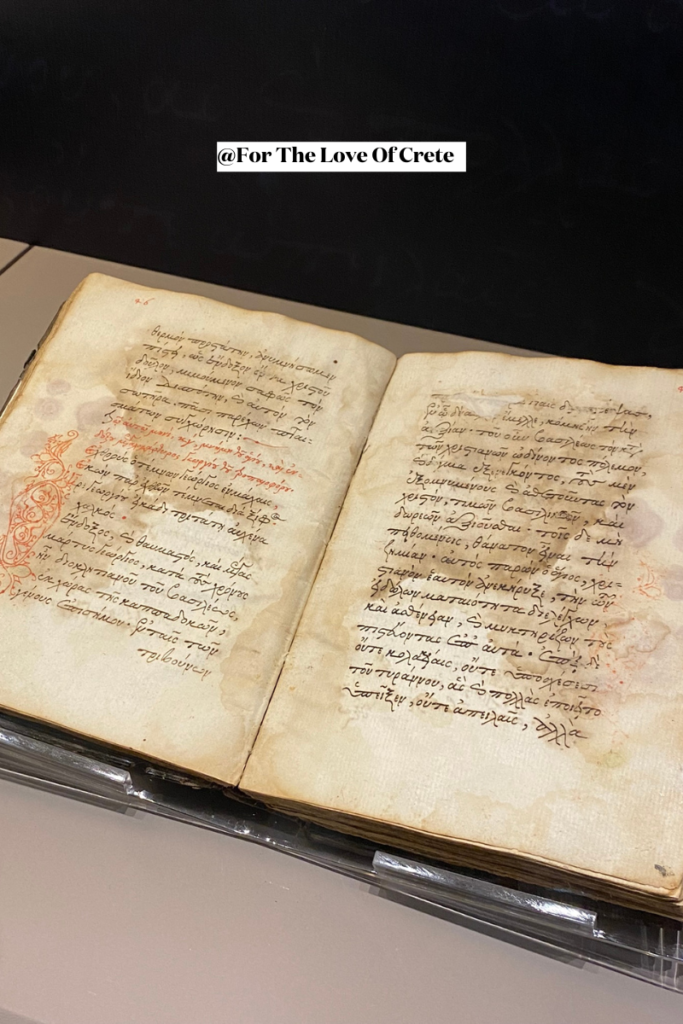

Since the 16th century, Arkadi Monastery stood as one of Crete’s most significant centers of science, art, and culture. In 2016, to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the monastery’s heroic self-sacrifice, a museum was established to house its extraordinary collection of surviving treasures: precious icons, liturgical items, and rare books dating back to 1629. These artifacts, many preserved from smaller dependent chapels and monastic houses, represent some of the finest examples of the Cretan School of art and craftsmanship.

The monasteries served as vibrant centers of education and craftsmanship:

- They maintained and funded local schools throughout the region

- Supported educational foundations under the Patriarchate’s guidance

- Operated as centers for manuscript copying and gold embroidery workshops

- Preserved arts education during the darkest years of occupation

- Preveli Monastery notably expanded its educational mission after 1831 under Bishop Nikodimus’s initiative

What made these monasteries truly remarkable was their sophisticated network of operations. Carefully selected monks maintained extensive information networks, providing shelter, guidance, and spiritual leadership to the local population. These holy men weren’t just religious figures – they were guardians of their people’s faith and culture, maintaining complex systems for gathering and sharing crucial information.

The monasteries also served as secure hideouts, with passages leading to the unconquered mountains of southern Crete. This physical connection to freedom made them natural gathering points where the local population could find both spiritual comfort and practical assistance in times of need. Their role as centers of resistance would continue well beyond the Ottoman period, with both monasteries playing crucial roles even during World War II.

This chapter of Cretan history shows how these monasteries became more than sanctuaries of faith – they were the command centers of cultural resistance, preserving not just religious artifacts but the very essence of Cretan Christian identity through generations of occupation.

4. Easter in the Shadows: Sacred Celebrations in Secret

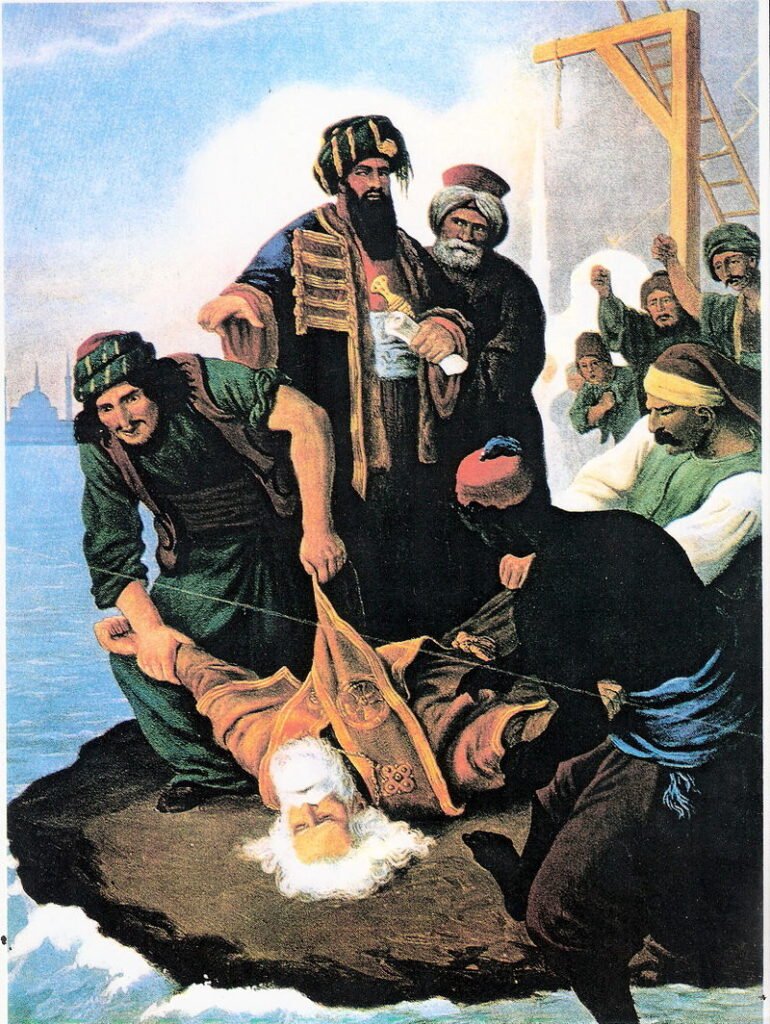

One of the most poignant chapters in Cretan history revolves around how families maintained their most sacred Christian celebration – Easter – during Ottoman rule. These celebrations required extraordinary caution and ingenuity, as the consequences of discovery could be severe. The gravity of such consequences was tragically demonstrated in Constantinople, where Greek Orthodox Patriarch Gregory V was publicly executed at the Patriarchate gate on Easter Sunday.

Despite foreseeing his fate, Gregory V had refused to flee, declaring “My death will be of more use than my life” and “The Patriarch of the Christians must die a Christian!” His body was left hanging for three days before being thrown into the sea – a stark reminder of the risks Christians faced during this period.

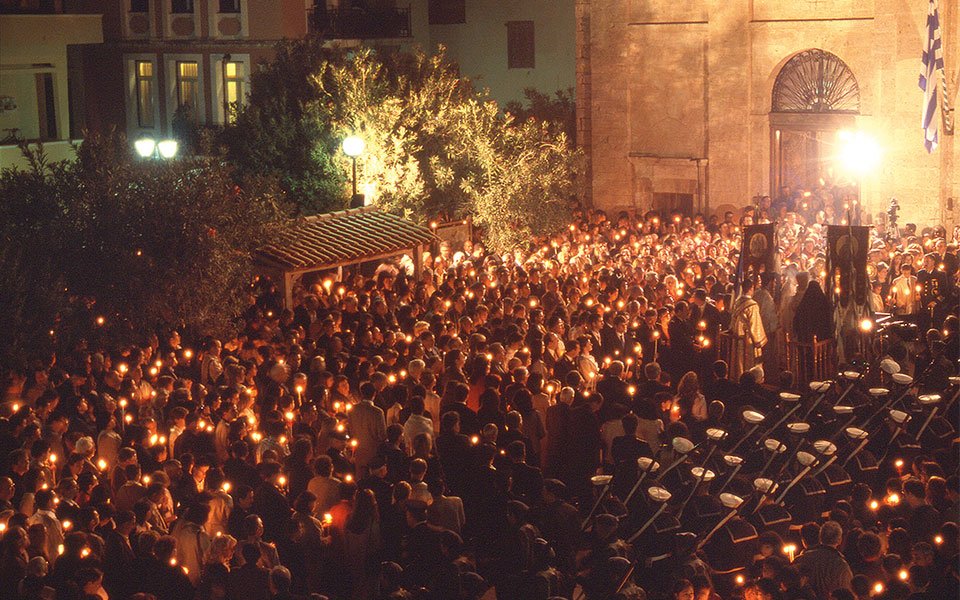

The faithful developed remarkable systems for preserving their Easter traditions. Christian families would coordinate their worship carefully, finding ways to maintain their sacred celebrations while avoiding detection. These weren’t just simple gatherings – they were full Easter services, maintained with all their spiritual significance despite the need for absolute secrecy.

Inside their homes, Cretan families quietly preserved essential Easter traditions:

- They dyed eggs red to symbolize Christ’s blood, a practice done behind closed doors

- Traditional tsoureki bread was baked with distinctive spices like cardamom, mahlab, and mastic

- The forty-day Lenten fast was maintained discretely

- Sacred items were carefully hidden away between celebrations

A particularly fascinating development in this period of Cretan history was the adaptation of religious practices to fit their dangerous circumstances. When access to parish priests became restricted under Ottoman rule, the Mystery of Unction was developed as an alternative to confession, allowing the faithful to maintain their spiritual practices without risking exposure.

5. Legacy of the Hidden Faithful: The End of an Era

The period following the 1856 Hatt-ı Hümayun reform decree revealed complex tensions in Cretan history rather than simple revelations. Many crypto-Christians had developed what scholars call “religious amphibianism” – a remarkable ability to navigate between two religious worlds, shaped by generations of living double lives. This survival mechanism helped preserve their true faith through decades of Ottoman rule.

The impact of crypto-Christianity went far beyond religious practice, becoming deeply intertwined with national identity. In fact, the majority of crypto-Christian narratives in the Ottoman Empire are linked to nationalism, where “crypto-Christianity” often paralleled “crypto-Greekness.” This connection grew particularly strong in Crete, where religious identity became inseparable from the struggle for independence.

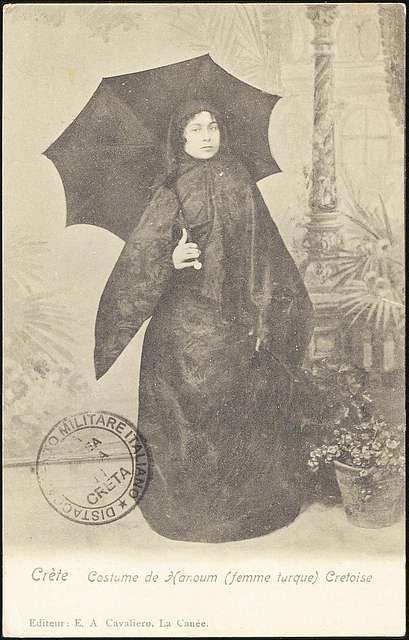

The period was marked by significant social and demographic changes:

- By 1881, Christians represented 76% of the population, with Cretan Turks reduced to 24%

- Strict Ottoman laws had only permitted marriages between Orthodox women and Muslim men, never the reverse

- Children of such marriages were required to be raised as Muslims

- Converts to Islam often faced harsh judgment from other Cretans, sometimes being labeled as “terrible Turko-Cretans” when forced to act against their own people

This turbulent chapter in Cretan history wasn’t characterized by peaceful religious coexistence, but rather by ongoing tensions, rebellions, and political upheaval. The crypto-Christian experience profoundly shaped the island’s journey toward independence, leaving an indelible mark on Cretan society’s evolution.

Living Legacy: How Crypto-Christians Shaped Modern Crete

The influence of Crete’s crypto-Christians continues to echo through modern Cretan culture, weaving threads of their resilient past into contemporary life. Many families still maintain private chapels in their homes – not from necessity as their ancestors did, but as a cherished tradition that connects them to their Cretan history. The practice of keeping an iconostasis (icon corner) remains a treasured feature in many Cretan households, though now proudly displayed rather than hidden.

Conclusion

When we look back at this remarkable chapter in Cretan history, we see far more than a story of religious perseverance. The crypto-Christians of Crete created an extraordinary legacy that continues to influence island life today. Through centuries of Ottoman rule, they didn’t merely survive – they developed sophisticated systems for preserving their faith, culture, and identity that would ultimately enrich the history of Crete in countless ways. From the hidden churches of Kapetaniana to the Kourmoulis family’s double life, from monastery networks to secret Easter celebrations, their story teaches us about human resilience and the power of community. Today, their influence lives on in Cretan architecture, family traditions, and religious practices – not as relics of the past, but as living traditions that continue to evolve and enrich Cretan culture, reminding us that even in the darkest times, people can find extraordinary ways to preserve what matters most to them.