When most people hear the name Nikos Kazantzakis, they immediately think of Zorba the Greek, but this towering figure of modern Greek literature created a legacy that extends far beyond his most famous character. Born in Crete and shaped by both Eastern and Western philosophical traditions, Kazantzakis fearlessly tackled life’s most profound questions through his novels, poetry, and travel writings. His works delve deep into human existence, spiritual struggle, and the quest for freedom in ways that continue to resonate with readers worldwide. As he once wrote, “Since we cannot change reality, let us change the eyes which see reality” – a sentiment that perfectly captures his revolutionary approach to literature and life itself.

The Making of a Literary Giant: Early Years in Crete

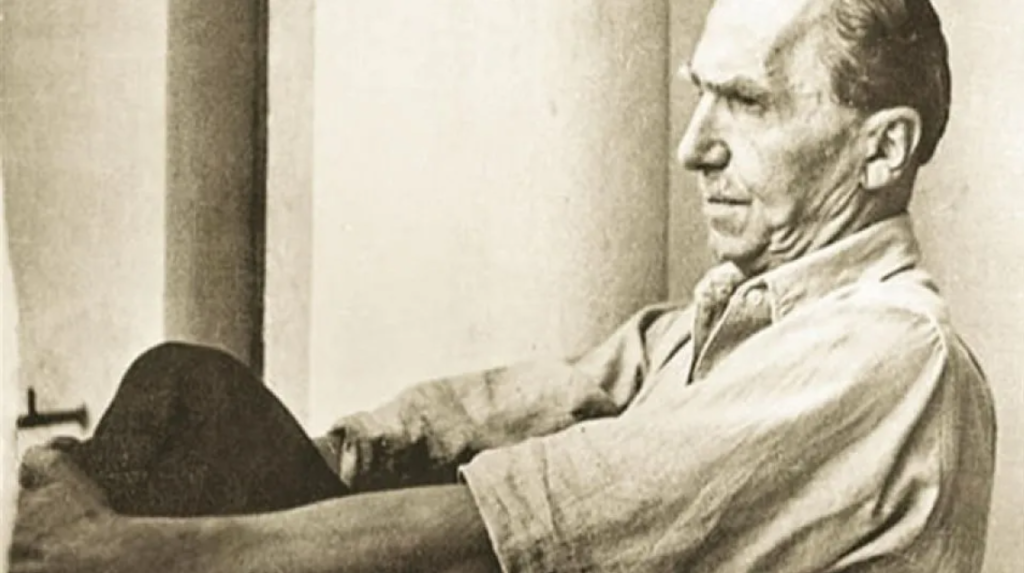

Nikos Kazantzakis drew his first breath on February 18, 1883, in Megalo Kastro (now Heraklion), Crete, while the island still lived under Ottoman rule. Few could have predicted that this merchant’s son would grow to become one of Greece’s most influential voices in literature. His childhood unfolded between two powerful influences – his father Michael, a strict and authoritarian figure from the village of Varvaroi (now Myrtia) who worked as a merchant and landowner, and his mother Maria Christodoulaki, from Assyroti in the Rethymnon prefecture, whose gentle spirituality provided balance and nurture. This family dynamic planted the seeds for his later explorations of contradiction and duality in human nature.

Growing up on this ancient island, young Nikos absorbed Crete’s rich cultural tapestry – from its folk traditions to its fierce revolutionary spirit. His early life wasn’t without turmoil; at age six, political rebellion forced his family to flee to Piraeus as refugees for six months. Later, in 1897, another uprising sent them to Naxos, where he attended the Franciscan School of the Holy Cross – an experience that sparked his lifelong fascination with both Eastern and Western philosophical traditions.

“I hope for nothing. I fear nothing. I am free” – these powerful words that would later grace his tombstone reflect the independent spirit that took root during these formative years in Crete, where he witnessed both the fierce pride of the island’s people and their struggles against occupation. The landscape itself – with its rugged mountains and sun-drenched olive groves – became embedded in his consciousness and would later emerge as vivid settings in his literary masterpieces.

A Scholar’s Journey: Education and Intellectual Formation

Kazantzakis’ intellectual journey evolved through a series of formative educational experiences that expanded his horizons far beyond his Cretan roots. The time at the Franciscan School had planted seeds of Western thought in his fertile mind, but it was just the beginning of his scholarly pursuits.

Upon returning to Heraklion in 1899, he completed his secondary education before moving to Athens in 1902 to pursue law studies at the University of Athens. His exceptional intellect earned him honors upon graduation in 1906, with his thesis on “Friedrich Nietzsche on the Philosophy of Law and the State” revealing the philosophical foundations that would underpin his literary career.

As he would later write, “True teachers are those who use themselves as bridges over which they invite their students to cross; then, having facilitated their crossing, joyfully collapse, encouraging them to create their own.”

The period from 1907 to 1909 proved transformative as Kazantzakis immersed himself in the intellectual atmosphere of Paris’s renowned Sorbonne. Here, philosopher Henri Bergson’s revolutionary ideas about time, consciousness, and creative evolution profoundly influenced his developing worldview. During these formative years, he refined his understanding of Nietzschean thought while synthesizing diverse philosophical traditions into what would become his unique literary voice. This blend of legal training and philosophical exploration created the intellectual framework from which his extraordinary body of work would later emerge.

Literary Masterpieces: Beyond Zorba the Greek

While most readers recognize Kazantzakis through “Zorba the Greek“, his literary universe extends far beyond this beloved masterpiece. His first step into the literary world came with his 1906 essay “The Disease of our Century”, published under the pseudonym Karma – an early glimpse of the fearless voice that would later challenge both religious and literary traditions.

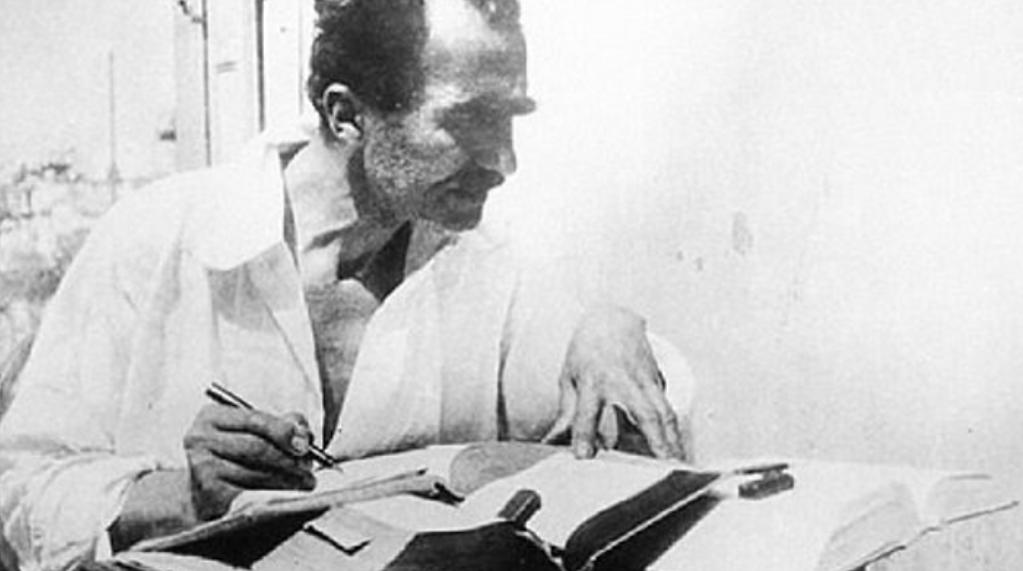

The true scope of his ambition revealed itself in his monumental “Odyssey: A Modern Sequel“, a staggering epic poem of 33,333 lines that demanded fourteen years of his life (1924-1938) and seven complete drafts before he considered it finished. This extraordinary work reimagines Homer’s hero in a fresh, existential light, following Odysseus beyond his return to Ithaca as he seeks deeper meaning in existence.

“Man is able, and has the duty, to reach the furthest point on the road he has chosen,” Kazantzakis wrote, seemingly describing his own relentless pursuit of literary perfection in this epic endeavor.

His novel “Zorba the Greek” (1946) brought him international acclaim, capturing the tension between intellectual restraint and passionate living through the unforgettable character of Alexis Zorba. Yet it was “The Last Temptation of Christ” (1955) that truly showcased his willingness to challenge orthodoxy, presenting Jesus as profoundly human in his spiritual struggles – a portrayal that sparked fierce controversy but solidified his reputation as a writer unafraid to explore life’s deepest questions.

Other significant works like “Christ Recrucified” (1954) and “Captain Michalis” (also known as “Freedom or Death”, published in 1953) further demonstrate his remarkable ability to blend philosophical depth with compelling storytelling, examining faith, freedom, and the human condition through characters who feel startlingly alive on the page. Each work reflects his unyielding commitment to exploring humanity’s most essential questions, making him not just a novelist but a literary philosopher whose words continue to provoke and inspire.

Philosophical Odyssey: Eastern and Western Influences

Throughout his intellectual journey, Kazantzakis wove together an intricate tapestry of Eastern and Western philosophical thought that profoundly shaped his worldview and literary vision. His early exposure to Nietzsche’s philosophy during his university years laid the foundation, but it was just the beginning of a lifelong exploration that would embrace seemingly contradictory traditions.

“God changes his appearance every second. Blessed is the man who can recognize him in all his disguises,” he wrote, reflecting his dynamic understanding of spirituality that transcended conventional religious boundaries. This sentiment emerged from his remarkable ability to synthesize diverse philosophical streams – from Buddha’s contemplative wisdom to Bergson’s vitalism, from Nietzsche’s will to power to Christian mysticism.

What makes Kazantzakis’ philosophical approach so unique is how he refused to see these traditions as opposing forces. Instead, he created a coherent vision that acknowledged the fundamental tensions of human existence while finding meaning within them. His works reveal a mind that could hold Lenin’s revolutionary spirit alongside Christ’s compassion, Spinoza’s rationalism next to Dante’s spiritual journey. Nietzsche’s powerful concept of the Dionysian and Apollonian visions of life particularly resonated with him, shaping his understanding of the creative struggle between order and chaos, reason and passion.

The famous epitaph on his tombstone – “I hope for nothing. I fear nothing. I am free” – perfectly encapsulates this philosophical synthesis, combining Western existentialist freedom with Eastern concepts of detachment. His bold choice to write in Demotic Greek rather than the more formal Katharevousa reflected not just a literary preference but a philosophical stance – bringing profound ideas into the language of everyday people. It’s this remarkable ability to bridge diverse philosophical traditions while remaining deeply rooted in his Cretan heritage that makes his work so universally appealing and enduringly relevant to readers seeking meaning in a complex world.

World Wanderer: Travels and Cultural Encounters

With an insatiable wanderlust that defined his creative spirit, Kazantzakis embarked on countless journeys that transformed his life experiences into rich literary tapestries. “Every perfect traveler always creates the country where he travels,” he once wrote – a sentiment that perfectly captured his approach to experiencing the world not just as an observer but as an active participant whose perception shaped reality.

His personal life reflected this same spirit of exploration. After a brief first marriage to Galatea Alexiou in 1911 that ended in 1916, he found his true life companion in Eleni Samiou, whom he met in 1924 and married in 1945. Eleni became not just his wife but his literary partner, supporting his work and managing his affairs throughout their journey together.

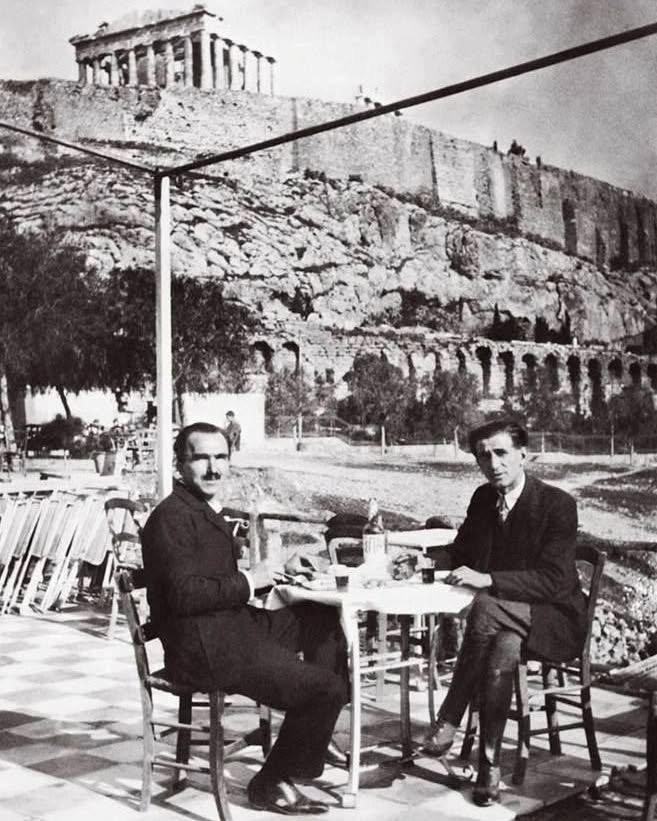

Kazantzakis’ travels took him from the bustling streets of China to the serene temples of Japan, where he worked as a foreign correspondent in 1935. These eastern journeys produced compelling works like “Japan-China: A Journal of Two Voyages to the Far East,” revealing his remarkable ability to absorb and interpret diverse cultures. His time in Spain during the Civil War similarly left deep impressions that would later emerge in his writing.

His wanderings weren’t limited to literary pursuits – briefly entering politics, he served as Minister without Portfolio in the Greek government from 1945-1946 and later worked as a UNESCO literary advisor, promoting cultural exchange across borders. Yet despite these formal roles, Kazantzakis remained at heart a seeker whose true home existed in the realm of ideas and whose citizenship was, in essence, universal.

The Soul of Greece: Cultural Impact and Artistic Vision

Beyond his global wanderings, Kazantzakis’ artistic vision emerged as a powerful force that captured Greece’s soul in ways few writers have matched. “A man needs a little madness, or else… he never dares cut the rope and be free,” he wrote – a statement that perfectly embodied both his creative philosophy and his impact on Greek culture.

If one word could encapsulate Kazantzakis’ literary essence, it would be the Greek concept of pathos – that profound emotional intensity that drives both art and life. His writing pulses with this pathos – passionate, raw, rebellious, unpredictable, and often mystical – mirroring the very soul of his beloved Crete with its rugged landscapes and fierce independent spirit.

His bold decision to write in Demotic Greek rather than the more formal Katharevousa wasn’t merely a stylistic choice but a revolutionary act that helped legitimize and enrich the everyday language of the Greek people. Through this choice, he brought profound philosophical questions into accessible form, democratizing ideas that might otherwise have remained in academic realms.

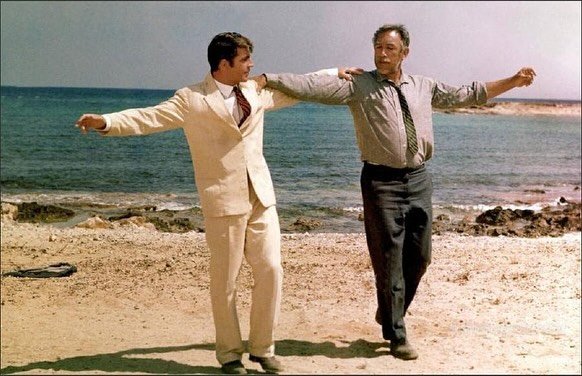

While he never won the Nobel Prize despite nine nominations, his impact transcends such accolades. His works, particularly when adapted to film, brought Greek culture to international audiences – the 1964 adaptation of “Zorba the Greek” creating an enduring cultural touchstone that continues to shape global perceptions of Greece.

Even controversy couldn’t diminish his cultural significance. When he died in 1957, thousands of Cretans gathered to honor him, despite the Orthodox Church’s resistance to his religious themes. Though buried outside the walls of Heraklion – not due to formal excommunication as often claimed, but because of clerical reluctance – this location has itself become symbolic of a man whose vision often extended beyond established boundaries.

Eternal Resonance: Modern Relevance and Global Recognition

Kazantzakis’ profound insights into human nature and the eternal questions of existence continue to captivate readers in the 21st century. “This is true happiness: to have no ambition and to work like a horse as if you had every ambition. To live far from men, not to need them and yet to love them,” he wrote – a paradoxical wisdom that speaks powerfully to our modern search for meaning and connection.

His masterwork “The Last Temptation of Christ” sparked renewed dialogue about faith and humanity when Martin Scorsese adapted it to film in 1988, introducing a new generation to Kazantzakis’ challenging spiritual vision. Meanwhile, “Zorba the Greek” remains a touchstone for discussions about living life to its fullest – its dance scene on the beach becoming an enduring symbol of embracing life despite tragedy.

Universities worldwide now offer courses dedicated to his work, and annual literary festivals celebrate his contributions to world literature. The Kazantzakis Museum in Myrtia, Crete, preserves his manuscripts and personal artifacts, drawing visitors from across the globe who seek deeper understanding of this literary giant.

Even in our digital age, Kazantzakis’ exploration of freedom, spirituality, and human potential speaks powerfully to new generations grappling with timeless questions. When modern readers encounter his work, they find not historical artifacts but living wisdom that continues to challenge, inspire, and transform – fulfilling his own vision of art’s purpose: “You have your brush, you have your colors, you paint the paradise, then in you go.”

Conclusion

When you explore Kazantzakis’ legacy today, you’ll find it resonates more powerfully than ever. His fearless questioning of faith, passionate celebration of life, and unique blend of Eastern and Western philosophical traditions continue to speak directly to contemporary readers seeking meaning in our complex world. From his reimagining of Odysseus to the spiritual challenges in “The Last Temptation of Christ,” from the life-affirming wisdom of Zorba to his deeply personal reflections on freedom, Kazantzakis invites us to engage with what it truly means to be human.

“For I realize today that it is a mortal sin to violate the great laws of nature. We should not hurry, we should not be impatient, but we should confidently obey the eternal rhythm.” This profound insight captures the essence of his genius – finding harmony within life’s natural patterns and embracing patience as a virtue in our hurried world. In engaging with his works, we don’t just encounter a historical literary figure but a timeless companion whose wisdom continues to illuminate our own journeys through life’s greatest mysteries.