On my first visit to Knossos, I hadn’t yet spent hours upon hours reading about the Minoans. I walked through those reconstructed corridors with wide eyes, my imagination running wild. Red columns rose against a blue sky. Painted dolphins seemed to swim across ancient walls. The plaques told confident stories about throne rooms and royal quarters, and I believed every word. Arthur Evans had built something powerful here, a stage where you could almost hear the rustle of ceremonial robes and smell the olive oil being poured for offerings. It felt real. It felt complete. It wasn’t until much later, after diving deep into the research and visiting the Heraklion Archaeological Museum, that I understood how much of what I’d seen was theatre.

If you want to see what the Minoans actually left behind, you need to visit that museum. There, under careful lighting, you’ll find the real frescoes, the original pottery, the jewelry and tools and sculptures that weren’t filtered through Evans’s romantic vision. The museum shows you fragments and lets them speak. Knossos shows you a stage set and calls it history.

Both matter. Both teach. But only one is honest about what we actually know.

In brief: fragments of a people who built ships and sailed them across the Mediterranean. Who gathered saffron and painted dolphins on their walls. Who developed plumbing systems that wouldn’t shame a modern hotel. Who left behind a script we still can’t read and a name we don’t actually know. We call them Minoans only because a 19th-century scholar named Karl Hoeck suggested the term, and Evans later popularized it, both men drawing from the myth of King Minos. It’s not their name. It’s ours.

So in this guide, let’s take a deep dive into who the Minoans really were, beyond the concrete and the painted guesses, and try to meet them on their own terms.

Where Does the Name “Minoan” Even Come From, and What Did They Really Call Themselves?

The label “Minoan” is a 19th-century invention. Karl Hoeck suggested it first, pulling from the Greek myth of King Minos and his labyrinth. Arthur Evans loved it and made it stick. But the people who lived in Bronze Age Crete never called themselves Minoans. Their neighbors knew them by other names. The Egyptians wrote of “Keftiu” in tomb paintings from around 1550 to 1292 BC, showing Cretans bringing gifts. The Hebrews called them “Kaftor” or “Caphtor” in biblical texts, preserving a memory of their Mediterranean presence. Mesopotamian records from 1800 to 1700 BC mention “Kaptara,” referring to traders and emissaries from the island. These names appear exactly when Minoan palaces were thriving, proof that the ancient world recognized them as a distinct, powerful people.

What they called themselves, we still don’t know. Their script, Linear A, remains undeciphered. Every prayer, every song, every administrative note sits locked behind symbols we can’t yet read. The silence is profound. A civilization that lasted over a thousand years, and we can’t speak their name.

Were the Minoans Actually From Crete?

For a long time, scholars speculated wildly about Minoan origins. Some proposed they sailed from Egypt. Others suggested North Africa or the Levant. Ancient DNA has settled the question. Studies published in Nature and other journals show that Minoans descended mainly from Neolithic farmers who arrived in Crete from western Anatolia (the coastal region of what is now Turkey, facing the Aegean Sea) and the Aegean thousands of years before the palaces rose. They also carried some ancestry from populations near the Caucasus and Iran, a common eastern thread in early Mediterranean peoples.

Here’s what makes them distinctive. The Minoans lacked something called “steppe ancestry,” a genetic signature from horse-riding pastoralists who swept across Europe from the regions north of the Black Sea. That migration reshaped the populations of mainland Greece and much of Europe. But it largely bypassed Crete. The Minoans developed in relative genetic isolation, rooted to their island for millennia. Recent studies found their gene pool remarkably homogeneous, suggesting a stable, long-settled population rather than waves of invaders replacing each other. They weren’t newcomers who arrived and built palaces. They were Cretans, shaped by their island over countless generations.

Are Modern Cretans Descended from the Minoans?

Yes. The same DNA studies that traced Minoan origins also found striking genetic continuity with modern populations. Today’s Greeks, especially those from Crete, cluster genetically close to both ancient Minoans and Mycenaeans. The bloodlines didn’t vanish. They were layered with later arrivals (Mycenaeans, Dorians, Romans, Venetians, Ottomans), but the ancient thread persists. When you sit in a mountain taverna and watch a Cretan grandmother arrange icons in her home shrine, or see a fisherman read the sea the way his ancestors did, you’re not just witnessing cultural echoes. There’s a genetic link running back four millennia. The Minoans didn’t disappear. They became Cretans.

What Did The Minoan World Actually Look Like?

Forget the image of a single palace on a hill. The Minoans built an entire network across Crete. Knossos was the largest, yes, but Phaistos rose in the south with its own grand courtyard and that mysterious clay disc we still can’t decipher. Malia stretched along the northern coast. Kato Zakros perched in the remote east, likely a hub for trade with Egypt and the Levant. Between these centers, smaller towns, rural villas, and farming estates dotted the landscape, all connected by roads. This wasn’t a kingdom with one shining capital. It was an island humming with interconnected communities.

Walk into a Minoan home of the elite and you’d find comforts that wouldn’t be seen again in Europe for thousands of years. Multi-storey buildings with light wells that flooded interior rooms with sun. Plastered walls painted in reds, blues, and yellows. Bathtubs. Toilets that could be flushed with water. Drainage systems running beneath the floors. The so-called “Queen’s Megaron” at Knossos (whatever it actually was) had a ventilation system to catch the breeze. These people understood how to live well. They valued light, air, cleanliness, and beauty in their everyday spaces.

Their tables held the ancestors of what Cretans still eat today. Olives and olive oil. Wine. Grain for bread. Honey from mountain hives. Cheese from sheep and goats. Legumes, figs, almonds. The great pithoi (storage jars taller than a person) found in palace magazines held olive oil and wine that likely fueled trade across the Mediterranean. And they dressed with care. Frescoes show women in elaborate flounced skirts and fitted bodices, men in belted kilts and jewelry. Gold, faience, carved stone. They loved color and craftsmanship. When you see the tiny golden bee pendant from Malia in the Heraklion museum, delicate and perfect after 3,700 years, you understand: these were people who poured skill and soul into beautiful things.

What Did a Day in Minoan Life Look Like?

We don’t have Minoan diaries. No one left us a schedule scratched into clay. But frescoes, tools, and household remains let us piece together a picture. Mornings likely began early, with bread baking in communal ovens and craftspeople settling into workshops. Potters shaped clay. Weavers worked their looms. Metalworkers hammered bronze into tools and weapons. Farmers tended olive groves and vineyards on the hillsides, while sailors loaded ships with oil and wine bound for Egypt or the Cyclades. In the harbor towns and palace courtyards, merchants haggled over goods, using standardized weights and sealed tokens to close their deals.

Evenings shifted toward the communal. Frescoes show feasting scenes, musicians playing lyres, dancers moving in procession. Children appear too, in art and in the small clay figurines and miniature tools archaeologists have found, suggesting they played, learned, and helped with lighter tasks around the home. Religious rituals wove through daily life, with small shrines tucked into houses for private offerings and larger ceremonies drawing communities together. It wasn’t so different, in rhythm, from the Crete you can still experience today: work in the morning sun, rest in the afternoon heat, gather with family and neighbors as the light fades.

Was Minoan Crete Really a Peaceful Paradise?

Arthur Evans loved this idea. A civilization that ruled the seas through trade, not conquest. Cities without defensive walls. Art filled with dolphins, flowers, and dancing, not soldiers and sieges. Compared to the fortress-citadels of the Mycenaeans or the massive walls of Near Eastern kingdoms, Minoan Crete looked gentle. Evans called it a thalassocracy, a peaceful empire of the sea. The image stuck. It’s still repeated in guidebooks and documentaries today.

The evidence tells a more complicated story. Archaeologists have found swords, spears, daggers, helmets made of boar’s tusk and bronze, shields, arrowheads. These appear in palaces and tombs alike. Skeletal remains show healed fractures and trauma consistent with violence. While the great palaces lacked monumental walls, the countryside tells a different tale: hilltop watchpoints, fortified farmhouses along the coast, small defensive structures positioned at strategic locations. Someone was watching for trouble. Someone expected it. And toward the end of their civilization, walls and fortifications appear more frequently at Minoan sites, possibly reflecting increased threats or growing instability.

So what do we make of this? The Minoans weren’t pacifists, but they weren’t the Mycenaeans either. They didn’t glorify war in their art. They may have channeled aggression into ritual spectacles like bull-leaping and boxing. Their control of maritime trade routes (though direct evidence for a large navy remains debated) likely served as a form of security, making Crete difficult to attack and keeping wealth flowing. Their approach to power looked different from their neighbors, less about walls and military display, more about trade dominance and social cohesion. Not a utopia. Not a warrior state. Something in between, and perhaps more interesting for it.

Did Women Really Rule Minoan Society?

This was another of Evans’s favourite ideas. He saw women everywhere in Minoan art: priestesses leading rituals, goddesses flanked by lions, female figures commanding ceremonial scenes. He concluded that Crete must have been a matriarchy, a society where women held political power. The theory captured imaginations, not just among feminist scholars but also alternative spiritual movements and travel writers. Modern academic consensus, however, is much more cautious.

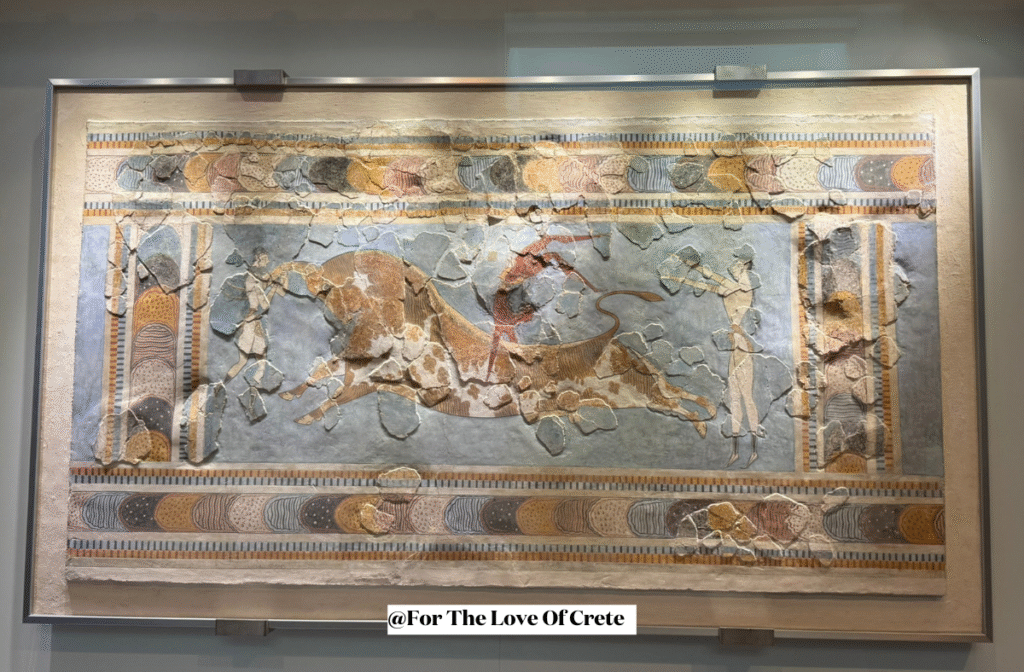

What the art actually shows is more interesting than a simple reversal of patriarchy. Women do appear prominently, far more than in most Bronze Age Mediterranean cultures. They lead religious processions. They handle sacred objects. In bull-leaping frescoes, young women vault over the horns alongside young men, trained for the same dangerous, prestigious ritual. This was not a society that kept women hidden or passive. But religious prominence is not the same as political rule. Priestesses wielding spiritual authority is not proof of queens holding governmental power.

Then there are the famous snake goddess figurines in the Heraklion Museum. They look striking and complete, but look closer. The larger figure’s flounced skirt is a modern reconstruction. The smaller figure had no head and little of her left arm. Evans’s restorer, Halvor Bagge, created a new head, a new arm, and extended the snakes beyond what survived. What you see is part ancient fragment, part 20th-century imagination. These figurines have shaped a century of assumptions about Minoan goddess worship. The assumptions may be right. But we should be honest about how much guesswork holds them together.

The truth is, we can’t read Minoan laws. Linear A stays silent. We don’t know how they passed down property, who sat on councils, or whether their rulers were men, women, or both. Centuries later, the Gortyn Code (a 5th-century BC legal inscription from Crete) shows that classical Cretan women could own property, inherit from parents, appear in court, and reclaim their assets after divorce. These rights were rare in the ancient Greek world. Whether such protections trace back to Minoan times, we can’t say for certain, but Crete clearly had a long tradition of distinctive laws regarding women. What we can say about the Minoans is this: their culture placed women at the center of religious and ceremonial life in ways that stand out across the ancient world. That matters. Whether it translated into political matriarchy, we simply don’t know.

What Did the Minoans Believe?

Their sacred words remain a mystery, but the images and spaces they left behind speak clearly enough.The Minoans were drawn to a goddess, possibly several, linked to nature, mountains, animals, and the wild forces of the earth. Male deities and sacred bulls appear too, especially in later periods, but they never dominate the way the female forms do. Small clay figurines show female figures with raised arms, sometimes holding snakes, sometimes flanked by birds or lions. Shrines appear everywhere: tucked into homes, built into palace complexes. Peak sanctuaries on Crete’s highest ridges drew worshippers who climbed for hours to leave offerings of clay animals, human figurines, and tiny bronze double-axes. Sacred caves, cool and dark, held rituals we can only guess at.

The sea mattered too. Octopuses spiral across Minoan pottery. Dolphins leap on palace walls. Shells and marine creatures appear in contexts that feel more than decorative. For a people whose wealth and power flowed from maritime trade, the ocean may have been as sacred as the mountains. Some frescoes show what scholars call “epiphany scenes,” a goddess appearing in or beside a tree, arriving as if summoned. Others depict processions, offerings, ecstatic gestures. Whatever they believed, it was woven into daily life, not separated into temples visited once a week. The sacred lived in their homes, on their hilltops, in the creatures of land and sea. We may never know the words they used, but the feeling comes through: reverence, connection, a world alive with meaning.

What About the Famous Bull-Leaping?

You’ve seen the image: a young athlete vaulting over the horns of a charging bull, body arched in mid-air, two companions steadying the scene. It’s the most iconic Minoan image we have, painted on palace walls from Knossos to Avaris in Egypt. What it meant is harder to pin down. Sport, initiation rite, religious offering, or all three at once? We don’t know. What we do know is that both young men and women performed it, judging by the frescoes. The act demanded extraordinary courage and training. Whether the athletes survived regularly or died often, whether the bulls were killed afterward or released, whether spectators cheered or prayed, these questions stay open. But the image itself tells us something true about Minoan values: grace under danger, skill made sacred, and a willingness to meet raw animal power face to face.

I’ve sometimes wondered if what we’re looking at is something like the original Olympic Games. Historians have noted the parallels: athletic prowess, ritual significance, public spectacle, young bodies pushed to their limits for something greater than personal glory. The Greeks who later created the Olympics may not have known they were echoing something older. But standing in front of that fresco in the Heraklion Museum, the connection feels hard to dismiss.

How Did the Minoans Write and Record Their World?

I’ve mentioned Linear A several times already, and there’s a reason it keeps coming up. It’s the locked door at the heart of everything we don’t know. The Minoans developed this script for administration, record-keeping, and possibly religious offerings. They used it for at least 500 years, scratching symbols onto clay tablets, seals, and libation vessels. Hundreds of examples survive, tantalisingly close to readable. But no one has cracked it. We can’t read their inventories, their dedications, their letters. After the Mycenaeans took control around 1450 BC, a new script appeared: Linear B. That one we can read. It turned out to be an early form of Greek, and it tells us about grain stores, livestock counts, offerings to gods. Bureaucratic details, not poetry or prayer. The Mycenaeans borrowed the Minoan writing system and adapted it for their own language. The transition marks more than a change in script. It signals a cultural takeover. The original Minoan words behind Linear A remain silent, still waiting for their translator.

What Brought the Minoans Down?

There was no single catastrophe. The Minoan decline came in waves, each one weakening what the previous had left standing. Around 1700 BC, earthquakes levelled palaces across the island. They rebuilt. Then came the eruption of Thera (the island we now call Santorini) sometime between 1620 and 1500 BC, one of the largest volcanic events in human history. The explosion sent tsunamis crashing into Crete’s northern coast and choked trade routes with ash. How much direct damage it caused remains debated, but the disruption to their maritime networks was real. Recent studies have added another layer: DNA evidence of plague (Yersinia pestis) and typhoid fever (Salmonella enterica) in Minoan remains. Disease stalked them too.

By around 1450 BC, something broke. Nearly every major palace on Crete was destroyed or abandoned, except Knossos. Fire swept through Phaistos, Malia, Zakros. Whether the final blow came from earthquakes, internal revolt, outside invasion, or some combination, we can’t say for certain. What we do know is who moved into the ruins. The Mycenaeans from mainland Greece took control of Knossos and, with it, the island’s remaining power. The Minoan world didn’t end in one dramatic collapse. It frayed, cracked, and was finally absorbed by newcomers who admired what the Minoans had built, even as they replaced them.

What Did the Mycenaeans Do to the Minoans?

The Mycenaeans came from mainland Greece. They built fortress-citadels, celebrated warriors in their art, and spoke an early form of Greek. By around 1450 BC, they had taken control of Knossos. Whether they arrived as conquerors, opportunists filling a vacuum, or something in between, the result was the same: Crete’s remaining centre of power now answered to mainlanders.

The takeover wasn’t pure destruction. The Mycenaeans admired Minoan culture. They borrowed its art styles, its religious symbols, possibly its administrative systems. They adapted Linear A into Linear B to record their own language. Minoan craftspeople likely continued working under new management. But the direction of influence had reversed. Where once Minoan fashions and techniques spread to the mainland, now Mycenaean Greek filled the tablets and Mycenaean elites sat in the old palaces. DNA from the Late Minoan cemetery at Armenoi shows some individuals with genetics closer to mainland populations, evidence that people moved, not just ideas.

Knossos continued for another two centuries under Mycenaean administration. Then it too fell, sometime around 1200 to 1100 BC, part of the wider Bronze Age collapse that swept away palace cultures across the eastern Mediterranean. The Hittites crumbled. Egyptian power contracted. Mycenaean citadels burned. Whatever combination of climate stress, migration, warfare, and systemic failure caused this broader collapse, Crete did not escape it. The palatial world the Minoans had built, and the Mycenaeans had inherited, finally went dark.

Did the Minoans Really “Disappear”?

This is the question I get asked most often when people learn about the Minoans. What happened to them? Where did they go? The answer is simpler and more profound than most expect: they didn’t go anywhere. The phrase “the end of Minoan civilization” doesn’t mean the people died out. It means their distinct way of life, their art, their script, their political structures, stopped being visible in the archaeological record. Cultural extinction is not the same as biological extinction.

The Minoans became something else. They absorbed Mycenaean rulers, then Dorian Greeks, then Romans, Byzantines, Venetians, Ottomans. Each wave added a layer, but the foundation persisted. The DNA evidence we discussed earlier confirms it: modern Cretans carry genetic signatures linking them to those Bronze Age ancestors. The bloodline survived, folded into later populations like dough folded into dough. When you watch a Cretan dance at a village festival, when you sit at a table where strangers become family over shared food and raki, when you notice how fiercely Cretans guard their traditions and their independence, you’re not seeing an echo of the Minoans. You’re seeing what they became.

Conclusion: Meeting the Minoans on Their Own Terms

We started this journey with a confession: my first visit to Knossos, I believed every painted column and confident plaque. I didn’t know how much was theatre. Now, after all this research, I believe something different. The real Minoans are more fascinating than Evans’s stage set ever was. Not because of what we can prove, but because of what remains after we strip away the guesses and the concrete. Fragments of a civilization that valued beauty, skill, and connection. People who looked out at the same mountains and the same sea that Cretans look out at today. We call them Minoans because we had to call them something. They called themselves something else, and that word is lost. But they’re not gone. Their spirit lingers. Their blood runs in Cretan veins. Their silence sits in museums, waiting. The Minoans are still here. You just have to know how to look.

Further reading:

16 Must-Visit Museums in Crete: From Ancient Wonders to Local Secrets

Nikos Kazantzakis: Exploring His Fascinating Life and Enduring Legacy Beyond Zorba

5 Fascinating Facts About The Cretan Dialect: The Living Heritage of Cretan Greek

You can learn much more about Crete and its full history, plus tons of other stuff, at secretcrete.com

Definitely checking it out. Thank you!

-Bella